Curious Conversations, a Research Podcast

"Curious Conversations" is a series of free-flowing conversations with Virginia Tech researchers that take place at the intersection of world-class research and everyday life.

Produced and hosted by Travis Williams, assistant director of marketing and communications for the Office of Research and Innovation, episodes feature university researchers sharing their expertise, motivations, the practical applications of their work in a format that more closely resembles chats at a cookout than classroom lectures. New episodes are shared each Tuesday.

“Curious Conversations” is available on Spotify, Apple, and YouTube.

If you know of an expert (or are that expert) who’d make for a great conversation, email Travis today.

Latest Episode

Austin Gray joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to talk about microplastics and the growing body of research about their impact on human and environmental health. He shared insights related to the public perception of plastic pollution, the history of microplastics, and the direction of future research. Gray also emphasizes the importance of approaching research as public service and the need for effective science communication.

(music)

Travis

During the past decade, the term microplastics has become very well publicized. You've probably seen it all over newscasts, and maybe you've even heard that you may have the equivalent of a plastic spoon and microplastics inside your body somewhere. I know I saw that, and it didn't exactly help me sleep easier at night. So though we don't yet have a microplastics themed marble fill in the term is out there everywhere and I'm curious how we should make sense of it. What do we actually know about microplastics? Where they come from? How abundant they are in our environments? And how are they influencing human health? And thankfully Virginia Tech's Austin Gray is an expert in this very subject and was kind enough to let me ask him all those questions and more. Austin is an assistant professor of biological sciences and an affiliate of Virginia Tech's Global Change Center. His research focuses on addressing questions related to environmental toxicology. And to do that, he uses a physical and ecological approach to examine the impact of legacy and emerging contaminants, including microplastics, nanoplastics, and pharmaceuticals resulting from human influence and addressing their risk to a variety of freshwater and marine organisms. So Austin and I talked a little bit about what microplastics are. He explained to me where they come from and kind of the unknowns about how abundant they may or may not be in our environment and why that's such a challenging picture to get a full grasp of. He also shared his insights on the public perception of plastic pollution and the history of microplastics, how that fits into that picture, as well as what he hopes the direction of future research is so that we can better understand this very complicated topic. and he also shared a little about his personal journey into this research, which I believe started with him saying he thought that studying microplastics was stupid. So you'll definitely want to hear how he grew from that. I'm Travis Williams and this is Virginia Tech's Curious Conversations.

Travis

Well, I want to talk to you about microplastics. Yes. And so I figured just a great place to start the conversation is simply what are microplastics? How should we understand those?

Austin

Yes. So microplastics are essentially these really small particles that come from larger plastic items like a plastic bottle or plastic bag or I, our analogy, I use the styrofoam cups. I'm from Charleston. So you go to the beach and if you walk around the beach, you'll see like cups within like the salt marsh or the seagrass area. And if you pick that cup up, it's going to have like these flakes that come off and rub on your fingers. And those themselves would be the actual microplastics. So the classical definition are particles that are less than five millimeter in size or any dimension. But again, microplastics become its own field of research across different types of groups of plastics, not just. consumer products like bags and bottles, also tire particles. So your tires, when you go and replace your tires, you replace them because the tread's worn down. They're basically bald. They're smooth. And what isn't really considered is as the tires being used and it's basically coming in contact with the road, it creates these small particles that fragment off and go into the environment. And tires by design, think roughly 19 % of tires are made up of plastic polymers. Hence why tires are now considered or are considered microplastic particles or another group of microplastics.

Travis

So it sounds like if I was to paraphrase, that microplastics or just where all this stuff goes that we have, like what it kind of turns into essentially tires got to go somewhere, right?

Austin

Yeah. And I think that's part of the misconception with plastics is when we see plastics, it's like, they take hundreds of thousands of years to break down. And that's true. That's the conversion of a plastic item into CO2 or water, which is what we call mineralization.

That process takes hundreds to thousands of years, but the decomposition is much faster and work that I've done and work that I did at the Citadel down in Charleston, South Carolina showed that it ranges between two to eight weeks and that's how fast it takes to start producing microplastics. So if you have a plastic item and somebody discards it through littering or through a storm event, it's only going to take two to eight weeks to start producing microplastics once it enters the environment.

What's really interesting is that although it may take thousands of years to mineralize or degrade completely, along a much shorter time scale, we're seeing microplastics being produced, which is, think some of the concern is that we have all these particles. They're pretty persistent. mean, plastics are part of everyday life. So it's not like people are just not using plastics. They're already out there. And the plastic litter that's already out there is fragmenting into these microplastics. And that's where it enters soil water, air, so all these different mechanisms that humans can be exposed to. And that's always the question people, I think, really care about is, well, what's the implication between being exposed to microplastics and adverse human health effects?

Travis

Yeah. And I definitely want to get there. I am curious, though, before we do that, what's the history of us even considering or thinking about microplastics? Because I don't know when the first time is I heard the word microplastics but it was not in the earlier part of my year. In fact, it was probably very recently. So when did we start worrying about it?

Austin

That's really interesting because I think in the past 20 years, the field has exploded. And especially when I started back in 2013, it was still pretty early. But the first reports of microplastics go back to 1972. There were studies out there in the ocean looking at these little plastic nurdles that were present within the ocean, but also in different organisms within the marine environment. And that's actually where it started going back into the seventies. And that's where we started seeing a lot of research being, not a lot, but the start of microplastic research. And like I said, because of advancements within technology sampling, I would say probably it exploded around maybe 2008. And that's when we really started more work, seeing more work coming out. And then from there it's just grown exponentially into so many different avenues. That's fascinating. I I wasn't reading a lot of scientific journals in the eighties when I was growing up. So maybe that's part of it, but I didn't know that either until I got into the literature and started looking into it. Well, do we know or do we have any grasp on how many microplastics are in our environments? I think there's estimates out there. I think it's highly cited. The one estimate that's always reported is within the marine environment of the ocean, there's 5.25 trurian pieces of plastics in the ocean. But even that, I think, is still somewhat of a conservative estimate just because of the sampling techniques.

the size fractions that they're able to actually get down to. And we've done some projections looking at more microplastics within the atmosphere of me and a collaborator, Dr. Jose Inferutin here at Virginia Tech. And we've done some predictive estimates showing within the atmosphere, we're seeing levels even above 5.25 trillion. So it's still, that aspect is growing, but yeah, I guess those are more conservative estimates of what we know about microplastics within the environment.

Travis

Is the challenge in figuring out how much is out there simply the size or are there other factors that make it challenging?

Austin

Size, instrumentation, the instrumentation you need to characterize plastics is expensive but also it limits a large group of scientists from being able to actually investigate those aspects meaning that you need some level of characterization because we have all these extraction procedures but what we don't always recover are plastics sometimes there's natural items there's textiles things from cotton, wool, Chitin, so many different cellulose as well because of cigarette butts. Cigarette butts are probably one of the biggest, I guess, contributors to litter and pollution. And those are typically made up of cellulose acetate. And so there's a lot of cellulose items out there in the environment as well. So when we go out and we sample, we don't always just get microplastics. And I think that's important to distinguish for the, I guess, public is not everything that we get is plastic. Sometimes it's natural.

Sometimes they're just things that come from laundering. So your clothing material, nylon fleece, polyester, those themselves are actually plastic polymers by design and by chemical characterization or signatures. So it's a multitude of different pathways or things in which plastics can enter the environment. But again, trying to get an understanding of how much is out there requires one, sophisticated techniques, but also monitoring studies and It's not a great deal of, guess, funding mechanisms that look at monitoring, which I think is important to look at monitoring, but there's just not a lot of mechanisms to really support long-term monitoring to see not just the occurrence of microplastics, but also how it's changing throughout time. you're definitely right about the cigarette buds. Every stoplight that I go to, if I look over to the side, it's, it's still very, very, very covered. And I don't really know why that is, particularly stoplights.

Travis

Well, what is it that got you interested in microplastics. What, what I read a quote about you that, that said a lot of this was based in your own curiosity. So I guess I'm curious, what about microplastics makes you curious?

Austin

Yeah. So I guess it goes back to my time when I started doing research in an aquatic talks lab at the Citadel with Dr. John Weinstein. And a lot of our work early on was not microplastics. We were doing a lot of green chemistry work, really cool work that I'm still very proud of and still do even now in my own lab testing the claims of green consumer products because we call it greenwashing. You get a product, it's clear, you see a tree. So consumers think they're going to do their part saving the environment. So they spend more money on those products, but there was no claims as to whether or not those products were better for the environment. And so early work that I did was actually that. And I remember me and another lab mate, Jontay Miller, we were present that work at conferences and we both got a lot of attention from certain representatives from the different industries that were not happy with our findings, particularly showing that, and this is back in like 2011 or 2013, that a lot of the green consumer products that we were testing in regards to being less toxic or more degradable in the environment, those claims weren't actually true. And I think that was for me a big kicker that even though we were a small school, small lab, very minimal resources, we were able to do research that really mattered and had an impact. And that's kind of where it started for me. And I was very dead set on continuing that kind of work. And I remember me and John and the late Dr. Steve Kleeney, who used to be at Clemson. passed away in 2016, but we were at a conference and John and Dr. Kleeney had a ID of microplastics. And I remember John asking me, Austin, what do you think about microplastics? And I was like, that's stupid. Nobody cares about plastics. And this is me like 21 years old, you know, maybe 22, no foresight into that realm and understanding that my life would be basically where I'm at now because of microplastic research. So it's just funny. And I could imagine how John felt telling the student, Hey, what do think about microplastics? And I tell him, Oh, that's stupid. Nobody cares. And then he fast forward 15 years later and that's the makeup of my lab research group. But I would say from there, again, of course, you know, because I trusted my mentor and I knew that he was going to send me and lead me in the right direction. We ended up doing early work, really foundational work in microplastics. And it taught me because John is really cool in how he approaches research. And I think that's become a part of my repertoire as well as I think of contaminants more so as a model. So a lot of my questions are more ecological or physiological. The contaminant is just a means to answer a question that ties into both of those realms, whether it's how it's affecting organisms or how it's affecting the environment or ecological processes. And I always tell my students, like, if microplastics were to shut down today and nobody cared, we could still operate because our lab isn't dependent just on plastics. So just a means to answer a certain question that we have. And I highlight that because I think sometimes it can get misconstrued and I come off more like a microplasticist. And that's not my training. would say it's just more so I've been able to incorporate my physio physiology training, my toxicological training, my ecological training, my biogeochemistry training from all my different mentors and advisors and supervisors to be able to answer really cool questions, but looking at contaminants mixed in that as well. So I think that's given me a really cool approach and that goes back to that curiosity where. I have a lot of, I think my mind works in a really cool way where I just have inspiration from random things. And it's really ever from sitting down at my computer. It's more so from I'll be with my wife and we'll be having a conversation and we'll be talking. She's a wildlife ecologist. So we talk about really interesting dynamics about the environment and wildlife and climate change. And I'll have an idea or I'll be playing with my son and he's very inquisitive, much like me at his age and he'll ask questions. Then that relates to an idea or I'll just be sitting in my room or watching a movie and an idea come and then I'll basically jot it down and then I'll go and explore. And I think that's a really fun part of research and why I enjoy the job so much is because it's really a chance for me to use a lot of my creativity in regards to a project or experimental design, but answering questions that are relevant to what the general audience or the general community wants to know.

And I think that's one of the cool parts. And plastics has been one of those muses where I've been able to do various types of approaches because it's just from a curious viewpoint of, well, I wonder about this. So I wonder how this is happening or no one's really delved more into this aspect of microplastics. Maybe I can do that. Let's develop that and see what comes out of that. So it's really fun. It's a good exercise for me.

Travis

That is awesome. I love that you allow kind of life to lead you to the kind of leads your curiosity, your life experiences, the things you're bumping into in life. I love that. I love that because it is very similar to the work that I think a lot of journalists and people in my field do with curiosity. So that's really, really cool. Well, you talked a little bit about your curiosity and how these things are impacting the environment and human beings. So what do we know about how contaminants and microplastics specifically are impacting me and my family and my neighbors?

Austin

Yeah. this is whenever I give a seminar, I always get these questions because I understand why. mean, think a lot of it is not to be negative, but I think there is a lot of sensationalism that comes with microplastic and plastic research. You'll see articles that say there's a spoonful of plastics in your brain or there's plastics within breast milk, plastics within the blood. And it's one thing to report that, but then everyday people want to know like, I harming my kids or my family because I'm using tub of wear, I'm using plastic goods and That's a really difficult thing to really, I guess, walk that tightrope because there's so much we don't know. And I hate to blame or put the blame on people. And I think that sometimes happens within our field where we go and we tell people that have so much that they're dealing with, they're dealing with life, they're dealing with jobs, they're dealing with raising a family, dealing with kids, dealing with all these different dynamics that happens in our everyday life. And we sometimes tell them, well, using that plastics is bad. And sometimes people just don't have the bandwidth or the space to think about that. And I think about my mom raising me and my brothers and having to deal with going to work and getting us where we needed to go and dealing with various health aspects. And the last thing she probably wanted to hear or wanted to be told is that she's harming us because of the plastic bags that she keeps in the home. And so I like to preface that because I don't think the blame should go to the people. I think the blame should be towards industry in regards to the amount of plastics that's being produced. The lack of plastics that are being recovered and recycled. Also a policy side, the lack of any type of legislative body or legislative, uh, I guess, document that requires better recovery of plastics from industry leaders. And these are the major ways in which we can curve and stop and start mitigating plastic pollution. But I don't think it should be directed towards individuals because it ultimately places the blame indirectly and unfairly. Because in most cases, plastics is such a part of our integral part of our environment, our society that. The mechanisms in which we solve that problem cannot be by blaming the individual or everyday consumer. And that's a stance that I believe in truly. so circling back to your question, yes, there are things that can be associated with plastics, but we can never truly say in my opinion that anything is directly caused just because of plastics. Reason why is because of the world we live in. mean, we have thousands of synthetic chemicals that are present within our water.

We have various types of pollutants that are present within our air. Our daily lives, our exposure, we're exposed to a multitude of things at certain doses and levels that may be non-toxic or harmful and those that may be harmful, but it's never ever going to be just because of plastics because we're consuming and we're exposed to so much more than that. But there are negative associations with plastics. One example is the study that came out a couple of years ago from the New England Journal of Medicine showing that microplastic particles within the bloodstream can actually become large within your arteries and it can allow for plaque buildup. And so you can get atherosclerosis or hardening of the arteries simply from microplastic particles that are within your blood tract that to your artery wall or internal wall to the arteries, allowing that plaque to build up and they harden. And that's something that is of concern, that's of interest that we don't know a great deal about that, but we do know there's evidence suggesting that there is an association between cardio vascular issues and microplastic exposure. Beyond that, going into the occurrence of microplastics in the body, the size fraction of microplastics in the body that can cause, I guess, downstream negative implications for cellular responses, those are still things that we're trying to figure out, mainly because the size fraction that can actually infiltrate into the cell will be nanoplastics. Those are particles that are small, far smaller than microplastics, but similar to the scope of the I guess where the state of the field is, there's a lot there we don't It goes back to sophistication of technology. It goes into the ability to actually measure and detect, but it also ties into, well, we got exposure doses and risk. And we have risk and we have harm. And a lot of our work earlier on, as we still do as toxicologists, is the central theme, the dose makes the poison. To understand risk, you gotta know what harms. So a lot of studies, we use concentrations that are above relevance and They have merit, those are needed, but those concentrations don't translate to what we are typically exposed to in our everyday life. So it makes making those conclusions really difficult, but it also highlights where the field is and it will advance. will continue to advance. And this is kind of a plug, I guess, why funding mechanisms are important because it allows for collaboration. It allows for different researchers of different backgrounds and expertise to come together. And it allows us to address these wicked problems in regards to microplastics in the body because then we can start really teasing apart, okay, at relevant concentrations, what kind of downstream effects are we noticing? What type of implications are we noticing within organisms? And then tie it into more human health implications. But I would say as of now, there are likely negative associations, to say that we have a full understanding would be false. It would be pretty obtuse to say that, we know exactly what's happening. I would say that there is some, there likely is negative associations and research has shown that but having a full grasp or breadth of exactly what's going on and what happens, we don't know. And I think that's important to be clear about as well is that as a field, we're still growing, we're still developing, and hopefully in 20 years, we'll be able to know more and be able to do a better job of understanding exposure and what's really the negative implications associated with that.

Travis

Well, I appreciate that I didn't feel plastic shamed in that part of the conversation as just a parent that is. Also always trying to balance all these different things because I feel that so much. So I could very much appreciate that perspective. I'm, curious what you, where would you like to see us maybe get to it? Sounds like there's a lot of information that we still need to go get. Yeah. In an ideal world, where would you like for us to get to? What are we chasing? I guess what's the golden goose?

Austin

Yeah. I ran into golden goose is essentially finding a more sustainable means of utilizing plastics. I think there's a lot of avenues. that we can address and some of them are being done here at Virgin Tech with upcycling plastics into other purposes. But one, one goes into the mitigation aspect of reducing the amount of plastics that are being produced and that are being released into the environment that are not recovered and recycled. I think I was shocked when I started this work and I found out that roughly 9 % of plastics globally are ever recycled, which for me growing up and you probably can remember in the nineties, the recycle, reduce, reuse, all those campaigns. You see all the recycling bins everywhere. I heard the Jack Johnson song. He sang a whole song about it. Yes. And it came as a great shock to find out that that was actually not happening. most likely was happening. And there's been some legislative bodies that have helped curve it, but plastics were simply sent to a recycling facility. They were packaged and they were shipped to another country. And then you find out out of the different, if you buy a plastic bottle, has a number, any item has a number at the bottom or somewhere, that's SBI code. And those SBI codes associated with a certain polymer type. And out of the various, I think seven SBI codes, only two are easily recycled within your facilities. The rest, certain ones like polystyrene cannot be upcycled efficiently because once you get to a certain temperature, it just becomes unusable. And so those are mechanisms of having better, I guess, policy in place to stop or limit the production, but also making sure that there is some emphasis on those industries and corporations to recover plastics. The next one being that there is some mechanism where we're actually using plastics that can have alternative uses or can be recycled because that allows for the life cycle of a plastic to go from being a single use item to being used multiple times, which benefits because we're not just taking a straw or a plastic cup and throwing it away and it goes into a landfill. We're reusing it more and more and allowing us to have more, I guess, extend the life of it. And then the other side of it goes into, think, I guess what we're going to is having, again, as I mentioned, I guess a more concerted research effort or funding mechanisms to ensure that we can answer questions in regards to plastics that aren't just looking at toxicity or negative effects, but looking at the breadth of it. Cause it may be that there's nothing happening or there's something that's a positive or something that's just neutral, but we don't do enough. We don't have enough support to really delve into that line of research where I think.

There's always this concern of wanting to see the negative where that may not happen. And I think that's okay too, because that happens more in science than we realize is there's things that just, we didn't see it at a relevant level. We didn't see the effect or we didn't notice any observable changes. And that's fine. And that should be translated and communicated to the public. And so I think those are, guess, summarizing it all. think those are the mechanisms into where I would like to see the field going towards efficient management and mitigation strategies that are done at a policy level towards corporation, ensuring that we utilize polymers that can be have multiple purposes and multiple uses, and also ensuring that we have mechanisms available to pursue research in various aspects of plastic and microplastic pollution, especially as nanoplastics becomes more of an emphasis and we're able to start delving more into that side of research.

Travis

Well, with your time in this field and all the research that you've done in this area, I'm curious, what's something that maybe you have shifted or started doing? What's a change that your research has brought about maybe for you personally?

Austin

I would say me and my wife, my wife probably did more of it and kind of led that charge, but just more so being conscious of our waste. I think that's the thing, not even just from a plastic standpoint, but just from a waste standpoint. How can we limit how much waste we're producing and how can we limit our footprint, I would say. So one of those is thinking of different like materials for like laundry and home cleaning products. Rather than buying those packets that you put in your dishwasher, those pods that you use in your washing machine, actually formulating our own. It's actually pretty inexpensive and you can get materials online or you can look up materials online and order them or go to Walmart or such. And so we make our own dish detergent. We make our own dish washing powder solutions. We make our own laundry detergents. And so those have been pretty cool to be able to just rather than relying on these packaging items that have so much waste ⁓ attached to it. We can just buy something and then we have them in our containers and we can use them over and over again. I think that's been pretty cool. Another aspect, I guess, is just being more conscious of, I think how we talk about plastics and that goes into what I mentioned earlier. I think earlier on I was very much, you know, I was a young researcher and I was really passionate. I didn't realize the harm that I was causing by, like you mentioned, blaming. Blaming making people feel smaller or lesser or being because I'm a scientist and I do XYZ, I know better than you. And I think that's dangerous because it creates a lack of trust. It makes people feel uncomfortable and it doesn't allow for there to be conversation or dialogue because these things are much more nuanced and a lot of our solutions are very nuanced and it's not just simple as just do XYZ. There's a lot of conversations that need to be had. And so I think when I engage with people and I talk with people about my work or about the broader impacts of the environment, Being more conscious of making sure that I meet people where they're at, rather than trying to bash people and make them feel bad. I understand that I myself do have a certain level of privilege because I am educated and an expert in the matter. That doesn't mean that it gives me the right to speak to people in a certain way. And I think that's something that outside of just plastic and waste and everything, I think in regards to how I engage people as everyday person, I think that's important because yes, people should be informed, but there's a way that how we do that. If we come at it from a hierarchy, we're better, we know more. So you should listen just from that standpoint. We're not going to reach people and any solution that we want to propose or try to do will be limited because we aren't meeting people where they are. And we aren't thinking about the empathetic human side of things. We're just, I know this, do this. And I don't think that's sufficient.

Travis

I think there's a saying that goes something like people don't care how much you know until they know how much you care. think there's a lot of truth to that.

Austin

Yeah, definitely. Like I said earlier on, remember going to presentations and talking about things in this really, I was young going to town hall meetings. were towns in South Carolina that were looking at banning plastic bags and plastic items. And we would go and speak and you know, you feel that that level of like level of ego. Yeah, I'm helping influence policy change. Then you realize there's a person that's working in a facility that has no say into these things that likely may lose their job because of that. Maybe there's somebody that's using plastics that is struggling with their own health and they don't have the bandwidth to even think about that. And it was more so through having conversations that I was able to recognize that and also going into my community and talking to people in my community. so that's why I say like now I have a much more kind of relaxed approach to it where it's not so much that I'm trying to make people do anything. I'm more so just communicating and if you want to know, I can tell you. And if you don't want to know, I can at least give you some informed information and you can decide what you want, but it's not from a, it's not a push. I would say. And so I think that's helped me be able to speak to different audiences, people from different backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. think those are things that are important. And I think that's the highlight of science itself, kind of like the article highlighted, is that we're public servants and we have to do a really good job communicating what we do and why it matters. But just in how we engage with the community itself, we have to be really conscious of that because if we're not, we can dissuade somebody very easily, attend somebody off negatively to anything that we say. just by starting a conversation with, well, I'm doctor. And for me, I'm like, I'm Austin. I think my community treats me like just Austin. And I think that helps me a lot just to be able to do my job, but to never, I guess, as they say, I don't believe the hype and I get, don't get too high on your own supply. Same idea. Like don't get too fully yourself that you can communicate with everyday people because that's who we see more than anything, more than going to conferences and more than talking to people in my department. I engage with the community and the community at large, most people. don't do what I do. And so if the approach is simply, do this, listen, it's not going to happen.

(music)

Travis

And thanks to Austin for helping us better understand microplastics and their influence on our environments. If you or someone you know would make for a great curious conversation, email me at traviskw at vt.edu. I'm Travis Williams, and this has been Virginia Tech's Curious Conversations.

(music)

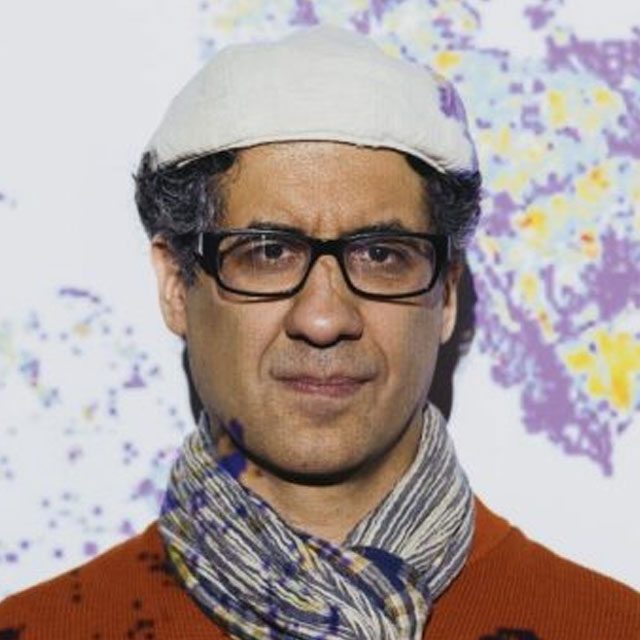

About Gray

Gray is an assistant professor of biological sciences and an affiliate of Virginia Tech’s Global Change Center. His research focuses on addressing questions related to environmental toxicology. He primarily uses physiological and ecological approaches to examine the impacts of legacy and emerging contaminants — microplastics, nanoplastics, and pharmaceuticals — resulting from human influence and assessing their risk to a variety of freshwater and marine organisms.

Past Episodes

-

General Item

The Mysteries of Microplastics with Austin Gray Date: Feb 23, 2026 -

The Mysteries of Microplastics with Austin Gray Date: Feb 23, 2026 - -

General Item

The Unknowns of Sharks with Francesco Ferretti Date: Feb 16, 2026 -

The Unknowns of Sharks with Francesco Ferretti Date: Feb 16, 2026 - -

General Item

Data Centers and Water with Landon Marston

Data Centers and Water with Landon MarstonLandon Marston discusses data centers and water use while exploring environmental impacts, cooling demands, and sustainable resource challenges.

Date: Feb 09, 2026 - -

General Item

Detecting Dark Matter with Patrick Huber

Detecting Dark Matter with Patrick HuberPatrick Huber joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to talk about world of neutrino physics and its implications for understanding dark matter.

Date: Feb 02, 2026 - -

General Item

Smart Mobility and the Future of Transportation with Mike Mollenhauer

Smart Mobility and the Future of Transportation with Mike MollenhauerMike Mollenhauer joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to talk about how smart mobility and infrastructure are influencing the future of transportation.

Date: Jan 26, 2026 -

-

General Item

The History of Christmas Music with Ariana Wyatt

The History of Christmas Music with Ariana WyattIn this Curious Conversations episode Ariana Wyatt delves into the history of Christmas music, from early carols to modern holiday hits.

Date: Dec 08, 2025 - -

General Item

3D Printing Homes with Andrew McCoy

3D Printing Homes with Andrew McCoyAndrew McCoy discusses how 3D-printed concrete homes could address housing scarcity and improve affordability in this Curious Conversations episode.

Date: Dec 01, 2025 - -

General Item

Banjo History with Patrick Salmons

Banjo History with Patrick SalmonsTune into Virginia Tech’s ‘Curious Conversations’ podcast - listen to Patrick Salmons explore the banjo’s origins, cultural history and evolving meaning.

Date: Nov 24, 2025 - -

General Item

Knee Injuries and Recovery with Robin Queen

Knee Injuries and Recovery with Robin QueenRobin Queen discusses ACL injuries, knee mechanics, and prevention and recovery strategies for athletes in this “Curious Conversations” podcast episode.

Date: Nov 17, 2025 - -

General Item

Black Bears and Observing Wildlife with Marcella Kelly

Black Bears and Observing Wildlife with Marcella KellyMarcella Kelly explores black bear behavior and wildlife observation techniques in a podcast episode about ecology and field research.

Date: Nov 10, 2025 - -

General Item

The History of Bed Bugs with Lindsay Miles

The History of Bed Bugs with Lindsay MilesIn this podcast episode, Lindsay Miles explores the genomics and urban evolution of bed bugs, uncovering what their history reveals about humans and pests.

Date: Nov 03, 2025 - -

General Item

The Cultural Significance of Ghosts with Shaily Patel

The Cultural Significance of Ghosts with Shaily PatelShaily Patel explores how ghost stories serve as cultural metaphors for trauma, memory and belonging in this podcast episode.

Date: Oct 27, 2025 - -

General Item

Adolescent Suicide, Screens, and Sleep with Abhishek Reddy

Adolescent Suicide, Screens, and Sleep with Abhishek ReddyAbhishek Reddy discusses how screen use, sleep patterns, and medication access relate to adolescent suicide risk and what families can do.

Date: Oct 20, 2025 - -

General Item

Drug Discovery and Weight Loss with Webster Santos

Drug Discovery and Weight Loss with Webster SantosWebster Santos discusses insights into drug discovery and weight-loss therapies, exploring scientific advances and health implications.

Date: Oct 13, 2025 - -

General Item

Exploring the Mind-Body Connection with Julia Basso

Exploring the Mind-Body Connection with Julia BassoIn this episode, Julia Basso explains how dance and movement practices link body and brain, exploring their effects on mood, health, and social connection.

Date: Oct 06, 2025 - -

General Item

Controlled Environment Agriculture with Mike Evans

Controlled Environment Agriculture with Mike EvansVirginia Tech’s Michael "Mike" Evans discusses innovations in controlled environment agriculture and their role in advancing sustainable food production.

Date: Sep 29, 2025 - -

General Item

Ecosystem Forecasting with Cayelan Carey

Ecosystem Forecasting with Cayelan CareyCayelan Carey explains how ecosystem forecasting helps predict water quality in lakes and reservoirs using sensor data and modeling tools.

Date: Sep 22, 2025 - -

General Item

Building Better with Bamboo with Jonas Hauptman

Building Better with Bamboo with Jonas HauptmanJonas Hauptman discusses his research into bamboo as a sustainable building material, exploring its challenges, non-traditional use, and potential for addressing housing needs.

Date: Sep 15, 2025 - -

General Item

The Future of 3D Printing with Chris Williams

The Future of 3D Printing with Chris WilliamsChris Williams explains how 3D printing differs from traditional methods, explores various materials, and discusses future applications.

Date: Sep 08, 2025 - -

General Item

Bacteriophages' Role in the Gut with Bryan Hsu

Bacteriophages' Role in the Gut with Bryan HsuBryan Hsu discusses bacteriophages, their role in gut health, and their potential in addressing antibiotic resistance through phage therapy.

Date: May 12, 2025 - -

General Item

Make Sense of Economic Climates with David Bieri

Make Sense of Economic Climates with David BieriDavid Bieri discusses the human side of economics, the value of historical context, and the importance of rethinking economic ideas and institutions.

Date: May 05, 2025 - -

General Item

The Magic of 'The Magic School Bus' with Matt Wisnioski and Michael Meindl

The Magic of 'The Magic School Bus' with Matt Wisnioski and Michael MeindlMatt Wisnioski and Michael Meindl explore how “The Magic School Bus” shaped science, education, and entertainment.

Date: Apr 28, 2025 - -

General Item

Using Virtual Reality to Explore History with Eiman Elgewely

Using Virtual Reality to Explore History with Eiman ElgewelyEiman Elgewely joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to talk about her work using virtual reality and the principles of interior design to explore historical spaces.

Date: Apr 21, 2025 - -

General Item

Ultra-Processed Foods with Alex DiFeliceantonio

Ultra-Processed Foods with Alex DiFeliceantonioAlex DiFeliceantonio discusses ultra-processed foods, their health impacts, and how dopamine influences food choices in Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations.

Date: Apr 14, 2025 - -

General Item

Technology’s Impact on the Appalachian Trail with Shalini Misra

Technology’s Impact on the Appalachian Trail with Shalini MisraShalini Misra explores how digital technologies are changing the Appalachian Trail, balancing tradition, accessibility, and environmental preservation.

Date: Apr 07, 2025 - -

General Item

The Dangers of Gaze Data with Brendan David-John

The Dangers of Gaze Data with Brendan David-JohnBrendan David-John discusses the use of gaze data in virtual and augmented reality, including privacy concerns and current mitigation research.

Date: Mar 31, 2025 - -

General Item

Community Dynamics During and After Disasters with Liesel Ritchie

Community Dynamics During and After Disasters with Liesel RitchieLiesel Ritchie discusses how sociology helps explain community resilience in disasters, the role of social capital, and the importance of local relationships.

Date: Mar 24, 2025 - -

General Item

Drone Regulation, Detection, and Mitigation with Tombo Jones

Drone Regulation, Detection, and Mitigation with Tombo JonesTombo Jones discusses drone regulations, safety, and counter UAS strategies, highlighting Virginia Tech’s role in advancing uncrewed aircraft systems.

Date: Mar 17, 2025 - -

General Item

Public Perception of Affordable Housing with Dustin Reed

Public Perception of Affordable Housing with Dustin ReedDustin Read discusses public perceptions of affordable housing, the role of profit status, and how development size impacts community support.

Date: Mar 10, 2025 - -

General Item

Unpacking the Complexities of Packaging with Laszlo Horvath

Unpacking the Complexities of Packaging with Laszlo HorvathLaszlo Horvath discusses packaging design complexities, including affordability, sustainability, and the impact of tariffs and supply chain disruptions.

Date: Mar 03, 2025 - -

General Item

Engineering Safer Airspace with Ella Atkins

Engineering Safer Airspace with Ella AtkinsElla Atkins discusses air travel safety, VFR vs. IFR challenges, recent collisions, and how technology and automation can enhance aviation safety.

Date: Feb 24, 2025 - -

General Item

Cancer-Fighting Bubbles with Eli Vlaisavljevich

Cancer-Fighting Bubbles with Eli VlaisavljevichEli Vlaisavljevich discusses histotripsy, an ultrasound therapy for cancer, its mechanics, clinical applications, and future directions in treatment.

Date: Feb 17, 2025 - -

General Item

Examining the ‘5 Love Languages’ with Louis Hickman

Examining the ‘5 Love Languages’ with Louis HickmanLouis Hickman discusses ‘The 5 Love Languages,’ their impact on relationships, research findings, and the role of personality, self-care, and adaptability.

Date: Feb 10, 2025 - -

General Item

The Behavior and Prevention of Wildfires with Adam Coates

The Behavior and Prevention of Wildfires with Adam CoatesAdam Coates explores the factors behind California wildfires, fire behavior science, urban challenges, and the role of prescribed burning in prevention.

Date: Feb 03, 2025 - -

General Item

Computer Security in the New Year with Matthew Hicks

Computer Security in the New Year with Matthew HicksMatthew Hicks discusses evolving computer security threats, AI-driven risks, and practical tips to stay secure in 2025.

Date: Jan 27, 2025 -

-

General Item

Internet of Things Safety and Gift Giving Tips with Christine Julien

Internet of Things Safety and Gift Giving Tips with Christine JulienChristine Julien discusses the Internet of Things, its definition, potential vulnerabilities, and the implications of using smart devices.

Date: Dec 09, 2024 - -

General Item

Neurodiversity and the Holidays with Lavinia Uscatescu and Hunter Tufarelli

Neurodiversity and the Holidays with Lavinia Uscatescu and Hunter TufarelliIn this episode the guests discuss neurodiversity during the holidays, exploring how traditions and social expectations affect differently wired minds.

Date: Dec 02, 2024 - -

General Item

AI and Better Classroom Discussions with Yan Chen

AI and Better Classroom Discussions with Yan ChenYan Chen discusses how AI can improve peer instruction and classroom discussions, using tools to help instructors monitor and support student engagement.

Date: Nov 25, 2024 - -

General Item

Forest Health and Natural Disasters with Carrie Fearer

Forest Health and Natural Disasters with Carrie FearerCarrie Fearer joins “Curious Conversations” to discuss forest health after natural disasters and ways to restore ecosystems.

Date: Nov 18, 2024 - -

General Item

Subduction Zones, Earthquakes, and Tsunamis with Tina Dura

Subduction Zones, Earthquakes, and Tsunamis with Tina DuraTina Dura talks about subduction zones, particularly the Cascadia Subduction Zone, earthquakes and tsunamis.

Date: Nov 11, 2024 - -

General Item

Turning Old Plastic into Soap with Guoliang “Greg” Liu

Turning Old Plastic into Soap with Guoliang “Greg” LiuIn this episode, Guoliang “Greg” Liu talks about his journey in sustainability, focusing on the innovative process of converting plastic waste into soap.

Date: Nov 04, 2024 - -

General Item

Emerging Technologies and Entrepreneurship with James Harder

Emerging Technologies and Entrepreneurship with James HarderJames Harder explores how emerging technologies fuel entrepreneurship and shape the future of startups in this Curious Conversations episode.

Date: Oct 28, 2024 - -

General Item

AI and Emergency Management with Shalini Misra

AI and Emergency Management with Shalini MisraIn this episode, Shalini Misra examines how artificial intelligence could support emergency management - from disaster planning to ethical use concerns.

Date: Oct 21, 2024 - -

General Item

Female Leaders of Nations and the U.S. Presidency with Farida Jalalzai

Female Leaders of Nations and the U.S. Presidency with Farida JalalzaiFarida Jalalzai explores female leadership worldwide and why no woman has yet held the U.S. presidency in this Curious Conversations podcast episode.

Date: Oct 14, 2024 - -

General Item

AI and Securing Water Systems with Feras Batarseh

AI and Securing Water Systems with Feras BatarsehIn this episode, Feras Batarseh discusses the intersection of water systems and technology, specifically focusing on aspects of artificial intelligence.

Date: Oct 07, 2024 - -

General Item

Alcohol Use and Intimate Partner Violence with Meagan Brem

Alcohol Use and Intimate Partner Violence with Meagan BremIn this episode, Meagan Brem talks about the intersection of alcohol use and intimate partner violence and the causal relationship between the two.

Date: Sep 30, 2024 - -

General Item

Brain Chemistry and Neuroeconomics with Read Montague

Brain Chemistry and Neuroeconomics with Read MontagueRead Montague explores how dopamine and serotonin shape decision-making, memory, mood, and motivation - the intersection of brain chemistry and neuroeconomics.

Date: Sep 23, 2024 - -

General Item

The Future of Wireless Networks with Lingjia Liu

The Future of Wireless Networks with Lingjia LiuLingjia Liu joins the "Curious Conversations" podcast to talk about the future of wireless networks.

Date: Sep 16, 2024 - -

General Item

The Mung Bean and Reducing Hunger in Senegal with Ozzie Abaye

The Mung Bean and Reducing Hunger in Senegal with Ozzie AbayeIn this episode, Ozzie Abaye notes her work using the mung bean to diversify the cropping system, empower farmers, and reduce hunger in Senegal, Africa.

Date: Sep 10, 2024 - -

General Item

Curbing the Threat of Invasive Species with Jacob Barney

Curbing the Threat of Invasive Species with Jacob BarneyIn this episode, Jacob Barney talks about invasive species, their impact on native species, and the challenges of managing them.

Date: Sep 02, 2024 - -

General Item

Making Motorcycle Riding Safer Around the Globe with Richard Hanowski

Making Motorcycle Riding Safer Around the Globe with Richard HanowskiIn this episode, Richard Hanowski talks about harnessing research to help make motorcycle riding safer in low- and middle-income countries.

Date: Aug 27, 2024 - -

General Item

The Evolution of Political Polling with Karen Hult

The Evolution of Political Polling with Karen HultIn this episode, Karen Hult discusses the history and evolution of polling, modern polling methods, and how to interpret poll results.

Date: Aug 20, 2024 - -

General Item

Navigating Back-to-School Emotions with Rosanna Breaux

Navigating Back-to-School Emotions with Rosanna BreauxIn this episode Rosanna Breaux discusses back-to-school emotions and strategies for students, parents, and educators.

Date: Aug 05, 2024 - -

General Item

Geologic Carbon Sequestration with Ryan Pollyea

Geologic Carbon Sequestration with Ryan PollyeaRyan Pollyea discusses geologic carbon sequestration, how it stores CO₂ underground and its role in climate change in this Curious Conversations episode.

Date: Jun 04, 2024 - -

General Item

Veterans and Mass Incarceration with Jason Higgins

Veterans and Mass Incarceration with Jason HigginsJason Higgins joins the "Curious Conversations" podcast to highlight the intersection of United States military veterans and mass incarceration.

Date: May 28, 2024 - -

General Item

Microplastics, the Ocean, and the Atmosphere with Hosein Foroutan

Microplastics, the Ocean, and the Atmosphere with Hosein ForoutanIn this episode Hosein Foroutan explores microplastics in the ocean and atmosphere - their sources, impacts, and what science can do about them.

Date: May 21, 2024 - -

General Item

Real Estate Values and Elections with Sherwood Clements

Real Estate Values and Elections with Sherwood ClementsClements examines how changes in home values may influence voter behavior - exploring the connection between real estate trends and presidential elections.

Date: May 14, 2024 - -

General Item

AI and the Hiring Process with Louis Hickman

AI and the Hiring Process with Louis HickmanIn this episode Louis Hickman discusses how artificial intelligence could influence hiring — from screening and bias to improving recruitment outcomes.

Date: May 06, 2024 - -

General Item

Exploring the Human-Dog Relationship with Courtney Sexton

Exploring the Human-Dog Relationship with Courtney SextonCourtney Sexton joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” podcast to talk about the unique relationship between humans and dogs.

Date: Apr 30, 2024 - -

General Item

The Chemistry of Earth History with Ben Gill

The Chemistry of Earth History with Ben GillBen Gill joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to chat about piecing together Earth history through a combination of geology and chemistry.

Date: Apr 23, 2024 - -

General Item

Circular Economies with Jennifer Russell

Circular Economies with Jennifer RussellJennifer Russell joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” podcast to talk about the concept of a circular economy.

Date: Apr 16, 2024 - -

General Item

The History of Virginia Tech's Helmet Lab with Stefan Duma

The History of Virginia Tech's Helmet Lab with Stefan DumaIn this Curious Conversations episode, Stefan Duma recounts the history of Virginia Tech’s Helmet Lab and its impact on head-injury research and safety.

Date: Apr 09, 2024 - -

General Item

The History of Food Waste with Anna Zeide

The History of Food Waste with Anna ZeideAnna Zeide joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to talk about the history of food waste in America and its impact on society and the environment.

Date: Apr 02, 2024 - -

General Item

The Dog Aging Project with Audrey Ruple

The Dog Aging Project with Audrey RupleIn this episode Audrey Ruple discusses the Dog Aging Project, exploring canine aging, health patterns, and what dogs can teach us about longevity.

Date: Mar 26, 2024 - -

General Item

All About Air Pollution with Gabriel Isaacman-VanWertz

All About Air Pollution with Gabriel Isaacman-VanWertzGabriel Isaacman-VanWertz joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to talk about air pollution and its misconceptions.

Date: Mar 19, 2024 - -

General Item

Righting a Wrong Understanding of Newton's Law with Daniel Hoek

Righting a Wrong Understanding of Newton's Law with Daniel HoekDaniel Hoek joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to talk about the recent discovery he made related to Newton's first law of motion.

Date: Mar 11, 2024 - -

General Item

Measuring the Risks of Sinking Land with Manoochehr Shirzaei

Measuring the Risks of Sinking Land with Manoochehr ShirzaeiManoochehr Shirzaei discusses land subsidence, its role in climate change, and how satellite data creates maps to guide local decisions.

Date: Mar 05, 2024 - -

General Item

Emerging Technology and Tourism with Zheng "Phil" Xiang

Emerging Technology and Tourism with Zheng "Phil" XiangZheng "Phil" Xiang joins the "Curious Conversations" podcast to talk about the intersection of technology and tourism.

Date: Feb 27, 2024 - -

General Item

AI and Education with Andrew Katz

AI and Education with Andrew KatzAndrew Katz explores how artificial intelligence could transform education, impacting teaching, feedback, and learning in this episode.

Date: Feb 20, 2024 - -

General Item

Warm, Fuzzy Feelings and Relationships with Rose Wesche

Warm, Fuzzy Feelings and Relationships with Rose WescheIn this Curious Conversations episode, Rose Wesche explores warm-fuzzy feelings and the science of relationships, from attachment to emotional connection.

Date: Feb 13, 2024 - -

General Item

The Future of Wireless Networks with Luiz DaSilva

The Future of Wireless Networks with Luiz DaSilvaIn this episode, Luiz DaSilva talks about wireless networks and Commonwealth Cyber Initiative's test beds.

Date: Feb 06, 2024 - -

General Item

The Positive Impacts of Bird Feeding with Ashley Dayer

The Positive Impacts of Bird Feeding with Ashley DayerAshley Dayer explores how bird feeding benefits human well-being and shares insights from a new project at the intersection of birds and people.

Date: Jan 30, 2024 - -

General Item

Sticking to Healthy Changes with Samantha Harden

Sticking to Healthy Changes with Samantha HardenSamantha Harden joined Virginia Tech’s “Curious Conversations” to chat about the science behind developing and keeping healthy habits.

Date: Jan 16, 2024 -

-

General Item

Screen Time and Young Children with Koeun Choi

Screen Time and Young Children with Koeun ChoiIn this episode, Koeun Choi discusses how media affects young children and shares a project using AI to support early reading development.

Date: Dec 11, 2023 - -

General Item

The History of Holiday Foods with Anna Zeide

The History of Holiday Foods with Anna ZeideAnna Zeide explores the history of winter holiday foods and how personal traditions surrounding them are created and evolve over time.

Date: Dec 04, 2023 - -

General Item

The Chemistry of Better Batteries with Feng Lin

The Chemistry of Better Batteries with Feng LinFeng Lin explains the chemistry of electric vehicle batteries, current production challenges, and how coal might contribute to future solutions.

Date: Nov 27, 2023 - -

General Item

AI as a Personal Assistant with Ismini Lourentzou

AI as a Personal Assistant with Ismini LourentzouIn this episode, Ismini Lourentzou discusses AI, personal assistants, and her student team’s experience in the Alexa Prize TaskBot Challenge 2.

Date: Nov 20, 2023 - -

General Item

The Power of International Collaborations with Roop Mahajan

The Power of International Collaborations with Roop MahajanRoop Mahajan discusses how international collaborations have advanced his graphene research their broader importance to innovation and scientific progress.

Date: Nov 13, 2023 - -

General Item

Driving around Heavy Trucks with Matt Camden and Scott Tidwell

Driving around Heavy Trucks with Matt Camden and Scott TidwellMatt Camden and Scott Tidwell discuss VTTI’s Sharing the Road program and share practical safety tips for drivers of all ages.

Date: Nov 06, 2023 - -

General Item

Autonomous Technology and Mining with Erik Westman

Autonomous Technology and Mining with Erik WestmanErik Westman explores how machine learning and autonomous tech are reshaping mining - and how Virginia Tech prepares students.

Date: Oct 30, 2023 - -

General Item

Agriculture Technology and Farmers with Maaz Gardezi

Agriculture Technology and Farmers with Maaz GardeziIn this episode, Maaz Gardezi discusses the importance of developing agricultural technology in collaboration with farmers and incorporating their input.

Date: Oct 23, 2023 - -

General Item

AI and Healthcare Workspaces with Sarah Henrickson Parker

AI and Healthcare Workspaces with Sarah Henrickson ParkerSarah Henrickson Parker discusses how AI and machine learning is currently used in some healthcare spaces, and what the potential is for the future.

Date: Oct 16, 2023 - -

General Item

AI and Online Threats with Bimal Viswanath

AI and Online Threats with Bimal ViswanathIn this episode, Bimal Viswanath discusses how the rise of artificial intelligence and large language models has changed the online threat landscape.

Date: Oct 09, 2023 - -

General Item

AI and the Workforce with Cayce Myers

AI and the Workforce with Cayce MyersIn this episode, Cayce Myers fields questions on artificial intelligence’s impact on the workforce, regulations, copyright law, and more.

Date: Oct 02, 2023 - -

General Item

Special Edition: The GAP Report with Tom Thompson and Jessica Agnew

Special Edition: The GAP Report with Tom Thompson and Jessica AgnewTom and Jessica from the GAP Report joined the podcast just prior to its 2023 release to explain what it is and how they hope it's used.

Date: Oct 01, 2023 - -

General Item

The Metaverse, Digital Twins, and Green AI with Walid Saad

The Metaverse, Digital Twins, and Green AI with Walid SaadIn this episode Walid Saad fields questions about the metaverse, digital twins, and artificial intelligence’s potential impact on the environment.

Date: Sep 24, 2023 - -

General Item

Semiconductors, Packaging, and more with Christina Dimarino

Semiconductors, Packaging, and more with Christina DimarinoChristina Dimarino discusses semiconductors, packaging in onshoring their production, and Virginia Tech's efforts for workforce development in this field.

Date: Sep 15, 2023 - -

General Item

Pilot: Electric Vehicles with Hesham Rakha

Pilot: Electric Vehicles with Hesham RakhaIn this pilot episode, Hesham Rakha shares insights on what sustainable mobility means and some of his personal experiences with an electric car.

Date: Aug 14, 2023 -

Podcast Host

About the Podcast

"Curious Conversations" is a series of free-flowing conversations with Virginia Tech researchers that take place at the intersection of world-class research and everyday life.

Produced and hosted by Virginia Tech writer and editor Travis Williams, university researchers share their expertise and motivations as well as the practical applications of their work in a format that more closely resembles chats at a cookout than classroom lectures. New episodes are shared each Tuesday.

If you know of an expert (or are that expert) who’d make for a great conversation, email Travis today.